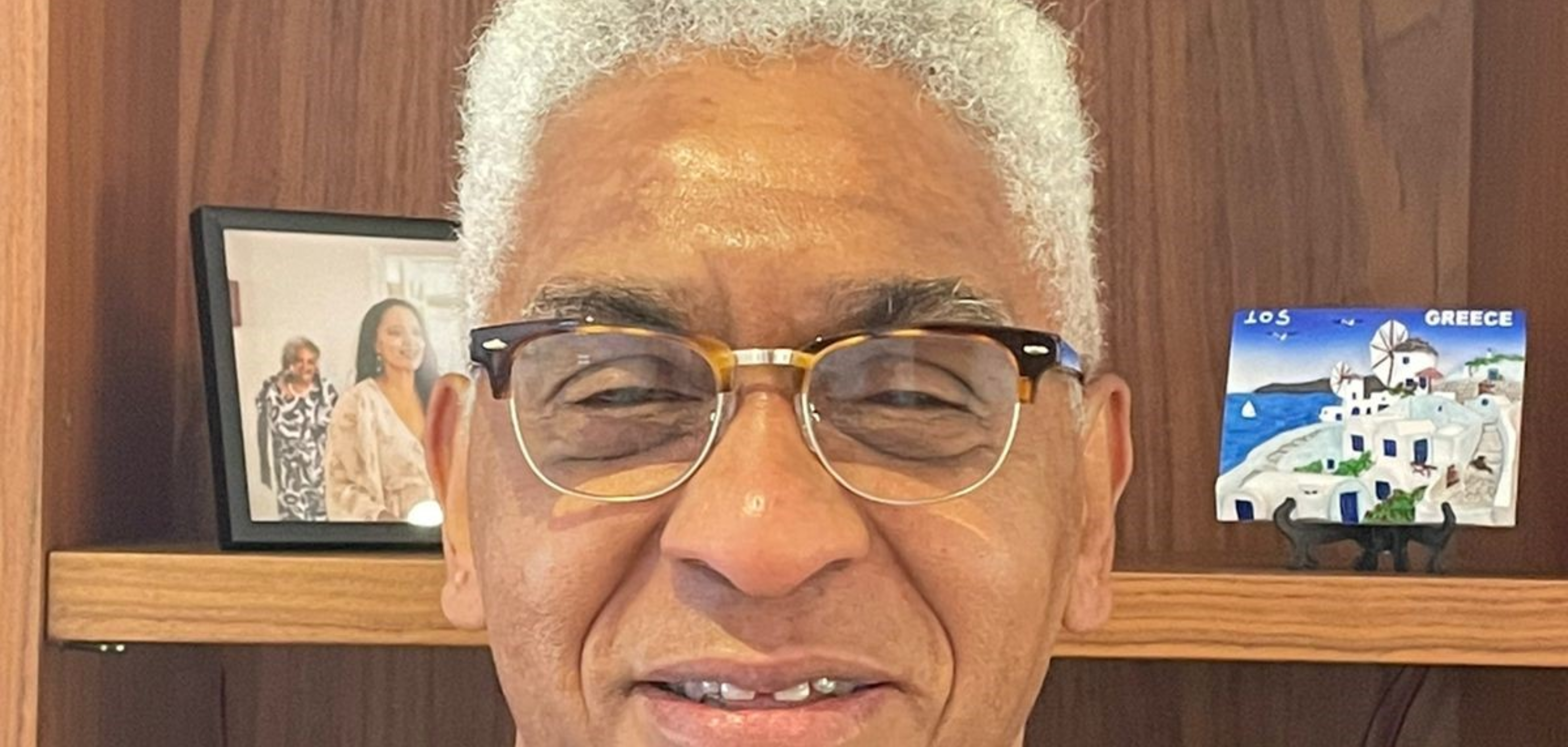

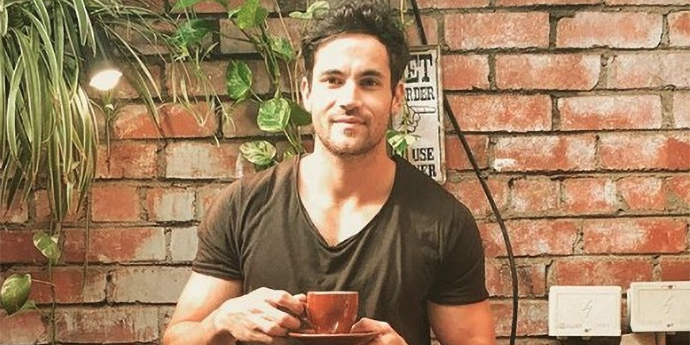

Cassim Motala considers himself an unlikely MBA candidate. He didn’t finish his undergraduate degree because he joined an internet gaming startup at a time when the gaming industry was exploding into the behemoth that it is today. At the age of only 23, he found himself managing 70 people – an all-consuming role in a ravenous sector.

“But not having a degree was always at the back of my mind,” he says, “so at the age of 27 I decided to do an MBA. But when I first applied the application was rejected on the grounds of my not having a undergraduate degree.”

As an entrepreneur, Motala was accustomed to curveballs and hurdles. He made an appointment with the head of admissions at the GSB, as well as the MBA programme director at the time, and made his case to join the programme: his passion, ambition, and experience would make up for his lack of formal academic qualification. They agreed to reconsider his application on condition that he provide a satisfactory standardized assessment score. Cassim rose to the challenge.

From Full Time to Part Time

Cassim first joined the full-time MBA Class of 2003 but quickly moved to the part-time class because he felt that his years of professional experience suited the cohort.

“It was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made,” he says. “The people in the part-time class were kind of in their late 30s, early 40s – that range. And they were doing real things. They were the captains of industry. So the wisdom and guidance they offered… they knew the stuff they were talking about. They weren’t talking from a theoretical perspective. And I think I learned the most from that. I was young, but I learned to listen. And that made the contents of the discussion, the interactions with the teacher very different. When people have real jobs, and no time, there’s no bullshit. And that played out in team dynamics, and in the work ethic. It was a matter of getting things done.”

At the time, the Modular MBA format [where students take blocks of time off work to study over a two-year period] did not exist. The part-time MBA option meant that you worked during the day and studied in the evenings and on weekends. An enormous – and frequently overwhelming – demand on the students’ time and capacity.

Cassim wasn’t working full time while he studied, which afforded him the time to join the Transformation Committee at the GSB. One of the topics the committee tackled was inclusivity, and the challenge was to increase the number of students applying for and studying at the GSB. Led by Dr Evan Gilbert, the initiative resulted in the Part-Time programme being replaced by the Modular option.

The birth of the Modular MBA

Fittingly for the GSB, the primary drivers of the change were values-based, with the School seeking to increase the number of black students and faculty at the School.

“We had three major stumbling blocks to inclusivity at the time,” recalls Motala. “The first one was that in Cape Town at the time 2001/2002 there weren’t a huge number of black people in mid- to senior-level positions in their companies.

“The second was that the GMAT was the sole standardized assessment accepted by the School. But we did a lot of research and we discovered that a GMAT was not as strong an indicator of performance as was assumed – there was not a huge correlation between a GMAT and performance on the programme. We did some learning diagnostic tests alongside the GMAT that showed that there was a strong bias towards English and mathematics. So the question was whether we could introduce some alternate tests.

“The third was location. Are people [based elsewhere] prepared to travel to Cape Town? Yes, there were. What was the optimal time period for them to be spending here, away from their jobs? What about affordability? Those were the questions that, if we could get the Modular programme at roughly the same price and quality, would affect its viability. Those types of considerations.”

Today, the GSB’s Modular programme is designed to allow those who have jobs, family commitments, or logistical constraints the opportunity to gain one of the most valuable, internationally recognized, and locally covered qualifications that any professional graduate can aspire to.

The hybrid model also allows for remote students to tailor their experience to their appetite for in-person or virtual learning – while enjoying the benefits of the campus as a hub for interpersonal interaction, and academic and technological resources.

Today the School also accepts a range of standardized assessments other than the GMAT [including the GRE, Executive Assessment, and NMAT tests], placing the GSB in line with its academic peers abroad, and widening the net for talented individuals to sign up for academic programmes that require an assessment.

Cassim Motala was not only there at the birth of these developments, but played a part in their delivery.

The GSB will always be a better place because of the contributions and involvement of its alumni. And if their combined efforts achieve what the School stands for, then South Africa will be a better place too – and export its values to the world.