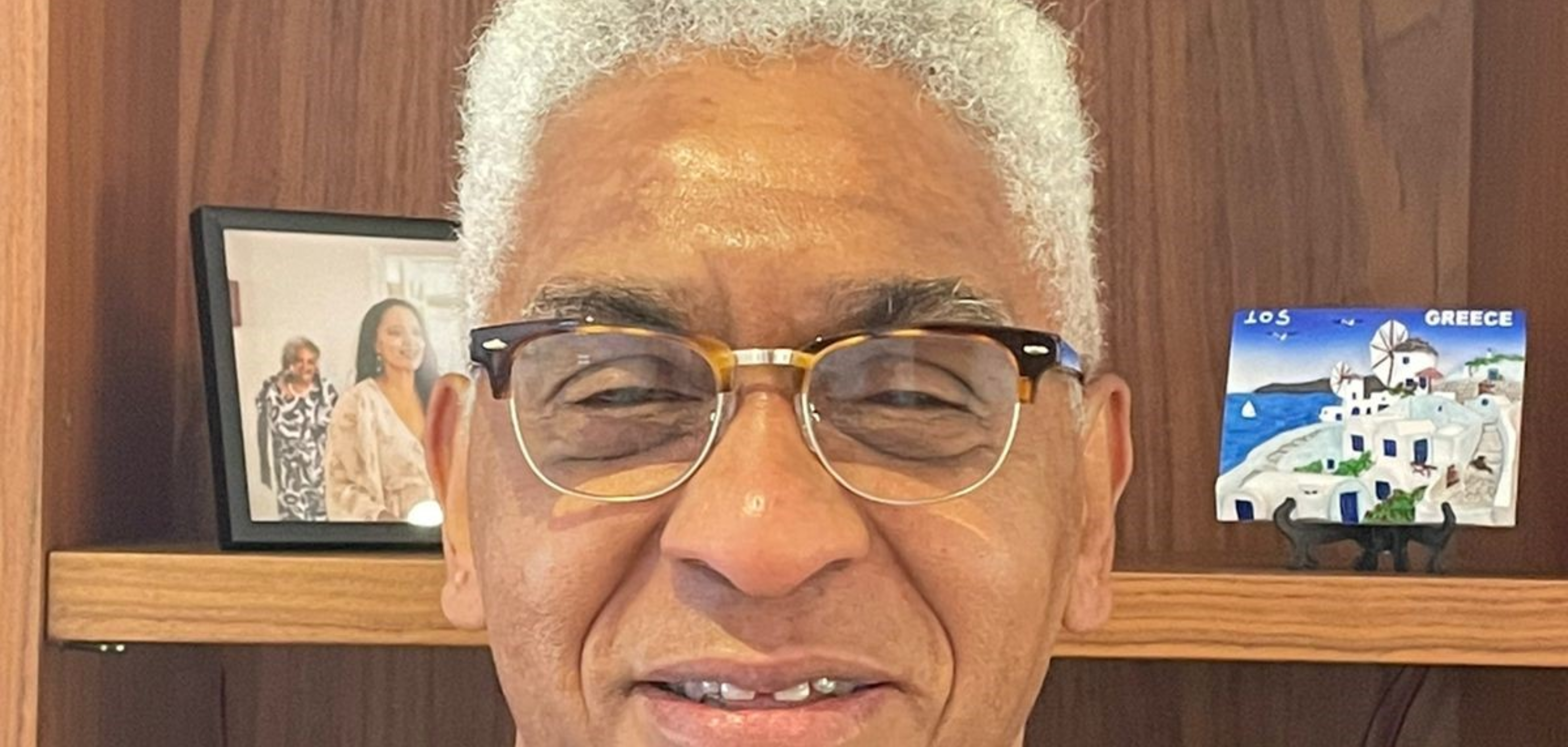

Whether it’s chasing higher pay or finding a working environment to suit your personality type, Dr Babar Dharani of the UCT GSB’s Allan Gray Centre for Values-Based Leadership spoke to Kieno Kammies at Cape Talk to explain what it is that keeps people happy at work. Dharani’s research identifies the organisational conditions that are associated with happiness at work, measured through: employee job satisfaction, effective job commitment and engagement levels.

Listen to the full podcast here

Q: How much does attitude play a role in a person’s happiness at work?

A: There’s a lot of non-scholarship research telling us that in order to remain positive, we need to look at the world with rose-tinted glasses, when in fact, empirical research tells us that overall, this is just a temporary measure to being happy at work.

If you’re unhappy, it’s better to vent, to say it out loud, rather than trying to see the positive in things all the time. Some people use alcohol to relax, and joining friends for a drink after work may seem like an opportunity to destress, but it’s the conversation with the friend that is more helpful than the drink itself. Actually a sprint would do much bigger wonders than anything else, because of the chemicals that make their way through your body when you exercise.

Q: Are organisations’ HR processes largely to blame for people’s unhappiness at work?

A: When you think about it, we spend virtually all our lives in organisations, from when we first start at nursery school, right through to living in retirement communities in our old age.

The HR processes in organisations do have a role to play in people’s job satisfaction. Employment hiring processes aren’t equipped to find out about the personal triggers that can make or break an office culture. People are hired based on their skill-sets rather than their personalities. There’s a definite shift happening in this area now, because organisations are realising that you can train people to develop their skills, but you can’t change their basic make-up.

There are several key factors that play a role in a person’s happiness at work:

Genetics — unfortunately this is predetermined and this is the factor about which you cannot really do much. Overall personality and attitude change is very minimal.

Personality-type — there is some room to manoeuvre here. Some people enjoy a military-style working environment whereas others prefer more casual surroundings. It’s therefore important to apply for jobs not purely based on salary.

Self-esteem — if you feel that you are doing something well, this improves your self-esteem. People tend to compare themselves with their same-sex parent and their peers. If you’re stacking shelves when your parents or peers are high-flying CEOs this will obviously impact the way you view yourself and your success in life.

Job-fit — the bottom line is try to choose a career that you actually enjoy.

Q: Could hierarchies at work be part of the problem? There’s that well-known adage that people don’t leave companies, they leave managers.

In my research conducted in South Africa, the lowest point of well-being and happiness in an organisation that I found, was due to exclusion. With South Africa’s history of exclusion, it’s so important that employers (and leaders) strive for inclusivity.

The late co-founder and chairman of South West Airlines, Herb Kelleher, famously said, “If you focus on your people, your mission statement is eternal.”

Certainly leadership is a subject that has been closely studied for decades. A leader is basically someone selected by followers who choose the leader based on the skills the leader possesses, that the followers deem necessary for their particular situation. Having a clear mission statement and vision is paramount. A lot of organisations that are owned by the proprietor of that organisation, have a very clear mission. But when leaders other than the proprietors run organisations, this can sometimes dwindle. The alignment of individual values to an organisation’s values translates into a source of dedication and commitment of the employees to the organisation, which can occur much faster when the proprietor is there because the proprietor embodies those values. So if the proprietor is all about inclusivity, it is going to be a part of the organisation. Where leaders are chasing the bottom line, sometimes those values can disappear. That’s why smaller organisations, with there is informal communication, and closer proximity to the leader, are statistically proven to result in happier employees compared to employees in impersonal, larger organisations.

Q: To finish. What would be your three pieces of advice to someone looking for more happiness in their work?

There are three major facets to happiness at work: satisfaction with the job, more positive emotions and less negative emotions at work. To achieve these three, try the following:

1. Take time to self-reflect to identify your interests, personal values and purpose, and work towards your personalised, tailor-made ‘subjective’ career success. Take care not to blindly chase societally-accepted ‘objective’ career success, such as high salary and an impressive job title.

2. Have an open conversation with your parents or guardians about their careers, and ask them to share their expectations about your future. Identify the differences between their and your personal goals and dreams in life. Such openness should psychologically assist to ensure satisfaction in your career choice and avoid dissatisfaction through comparisons with your parents or peers.

3. Worst amongst negative emotions are those felt when we feel marginalised or excluded. Find the courage to diplomatically speak up about the things that matter to you at work with your supervisors and with peers who make you feel excluded. Try to spot those individuals in any group who are being excluded and find ways to engage with them.