This concern manifests differently in different regions ranging from the Occupy Wall Street social movements in the US in 2011, or Black Lives Matter which has resonated worldwide, to protests, uprisings and unrest in many parts of the developing world associated with inequality.

When efforts to address the sources of inequality are purportedly “successful” and result in political and institutional transitions, our research published in the Journal of Management Studies, asks how and why does inequality manage to be reproduced? And what role do organizations play in maintaining exploitative labor institutions?

To answer these questions, we zoom in on a particular case of conflict in South Africa: The 2012-2013 farmworker strikes in the Western Cape, where protests turned violent over a protracted period. After centuries of colonial and apartheid policies that institutionalized racial oppression and inequality, South Africa’s 1994 democratic transition was intended to usher in a new era that would undo this legacy and promote equality. Yet inequality has continued to rise and the country’s Gini coefficient of 0.66 makes it the most unequal worldwide. Our research uses a case study design with multiple data collection processes, including face-to-face semi-structured interviews with farmworkers, farmers and key stakeholders that were active participants in the conflict, as well as focus groups and archival research.

Our findings provide an institutional logics explanation for why we see stubborn systems of inequality and oppression maintained even after transitions that ostensibly were focused on addressing the sources of that inequality. They also show how actors and organizations can exhibit and constrain agency, legitimating unequal access to resources and opportunities and why this can result in the persistence of inequality.

New but the same - Incomplete institutional change

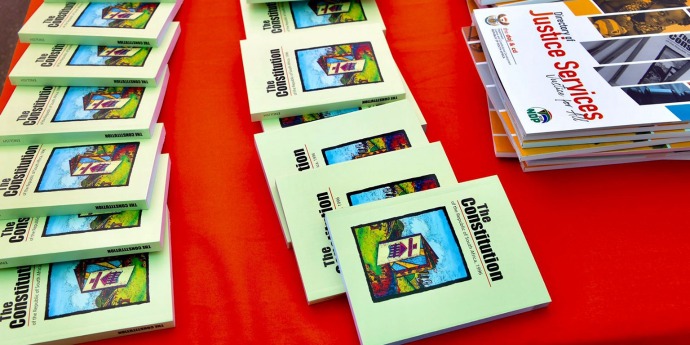

In the South African case, the transition from apartheid to democracy in 1994, which culminated in the adoption of a liberal constitution in 1996, presented a new set of rules that entrenched de jure protections and an extensive Bill of Rights including socio-economic rights. For the oppressed, the new institutional dispensation promised the beginning of equality, and yet approaching 27 years afterwards, the de facto rules often mirror the gross inequality of apartheid with many questioning the incomplete nature of the transition. As one of our participants explained, “How can we speak about a new democracy?… Apartheid is just now in a different way. It is still apartheid.”

Contradictory logics - A clash between the persistence of the old and the embedding of the new

The tensions between de facto and de jure institutions had been building up for years and culminated in various violent conflicts in 2012, with the farmworkers’ strike being one of the most prominent. Although the immediate cause of this conflict was associated with working conditions and wages on farms in the region, it was also representative of the complex and often conflicting dynamics between the persistence of the old and the challenge of embedding the new, as actors contested legacy socio-economic conditions and inequality.

Within our case study distinct contradictory logics manifested. The incumbent apartheid logic, which institutionalized a system of racial hierarchies, pervaded the present. The 1994 settlement and its protection of existing property rights in effect froze economic relationships at a point in time between the owners of capital (historically contingent) and the workers (racially defined and previously dispossessed). As a result, market logics legitimized old practices by highlighting the importance of economic and food security to the functioning of the overall system. Challenging the market logic was a social justice logic against the maintenance of the status quo and seeking equality not only in terms of political rights but also economically.

Market logics as “cover” for the maintenance of the old

In our case, farmers framed their reluctance to fully accede to workers’ demands based on a business imperative and market logic. They saw the conflict as an attempt to undermine their property rights and part of a wider political orchestration. In their search for a market solution, they increasingly resorted to outsourcing and short-term labor contracts to circumvent laws seeking to protect farmworkers. They engaged in limited negotiations with the ‘old’ farmworkers, drawing on a historically defined paternalistic relationship, thereby cutting through some of the workers’ solidarity and muddying workers’ community logics. This allowed partial provision of some socio-economic rights but with limited boundary conditions attached to this historical relationship. This increased the tensions between insiders and outsiders within the conflict, allowing for the dissipation of opposition and the maintenance of the institutional status quo. The result is that while the underlying logics of the apartheid and post-apartheid institutions may be differently constructed, with the former being underpinned by racist, nationalist ideology, and the latter by the market logic of profit maximization, the end outcome from our workers’ perspective at a de facto level looks disappointingly similar as both systems default to an exploitation of cheap labor.

Our findings highlight how systems of oppression and exploitation are perpetuated, often under the cloak of the legitimacy provided by the discourse of the supremacy of markets. Arguments around economic efficiencies and the paramount importance of property rights are invoked as being essential to investment decisions, with the resultant levels of inequality justified as meritocratic outcomes of effort and abilities. The market logic legitimization in turn makes it more “acceptable” to see the persistence of inequality accounting for its perpetuation.

Our case shows the difficulties associated with establishing new institutional frameworks and the stubbornness of institutional inequality as societies accumulate special interests with little incentive to adjust and every incentive to maintain the status quo systems of inequality. Although our case focuses on South Africa, we see similar struggles in other parts of the world as change struggles to take hold. Our research points to the importance for management scholars to engage in interdisciplinary studies of inequality, and particularly racial inequality, and its institutional dimensions.

Ansellia Adams

Ansellia Adams has a background in political economy and development and currently works as an analyst. Her work focuses on the nexus between institutions and development outcomes in developing regions.

John Luiz

John Luiz is a Professor of International Management at the University of Sussex in the UK and the University of Cape Town in South Africa. His research focuses on the interrelationship between multinational enterprises and institutions in developing countries.