While many worry the newly-launched African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) may harm Africa-China relations, more attention should be given to improving ease of doing business for local and Chinese businesses alike.

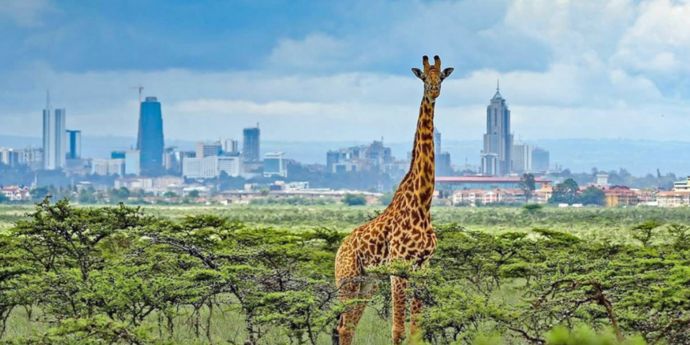

SA Trade Industry and Competition Deputy Minister Fikile Majola recently said that a strong foundation must be built to ensure inclusive economic growth in Africa and to help the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) become a platform for trade on the continent. Launched on 1 January, AfCFTA — once operational — could be the largest free trade area in the world based on the number of countries involved, linking 1.3 billion people with a combined GDP of $3.4trillion.

Conversations around AfCFTA are increasingly looking at the biggest challenges that need to be addressed to unlock the promise of intracontinental trade. Some commentators are also wondering how it will affect China, the world’s largest exporter and second-largest importer of goods. One report went so far as to suggest it could negatively affect relations with China, currently responsible for setting up much of the infrastructure for trade on the continent.

There have even been suggestions that AfCFTA may put Chinese and African trade interests in competition. Dennis Juru, president of the International Cross Border Traders Association, based in South Africa, has said, “The mindset of AfCFTA doesn’t work. As cross-border traders, we know China moves our goods in a cheaper way than anyone else.”

At the heart of these arguments lies a common conceptual confusion. China is not the largest source of foreign direct investment in Africa — nor is it the largest investor in African infrastructure. It is certainly the largest source of public sector borrowing where at least 80% of the US$ 153 billion lent to African countries between 2000 and 2019 financed infrastructure projects, mainly roads and bridges, power, telecoms and water. These loans normally stipulate that Chinese construction companies are given the contract to build the projects. Over 60% of infrastructure continent-wide and over 90% in Zambia is built with this funding from Chinese financial institutions. These loans will have to be paid back — with interest — at rates agreed to by the relevant African authorities.

At the moment, Africa is also a relatively small market in terms of Chinese manufactured goods, which mostly head to the US, Europe and the rest of Asia. Even as a source of raw materials, Africa provides less to China than Australia. It therefore seems somewhat of a jump to see a new Chinese peril when the facts show that Africa is not at the top of Beijing's economic agenda. I would agree with Stephen Chan, professor of world politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, who says in the Africa Report that Chinese manufacturers will not be too bothered by increased African manufacturing outcompeting domestic factories.

It must also be noted that it is not the huge Chinese SOEs (which dominate headlines and whose investments are politically directed) that make a difference to African economic growth and job creation. Rather, it is the thousands of small and medium Chinese enterprises — most of them in manufacturing in Africa — that are making a measurable impact on improving lives in Africa.

According to a comprehensive McKinsey report, published in 2017, there are an estimated 10 000-plus Chinese-owned firms operating across the continent, mainly in South Africa, Zambia, Angola, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia and Nigeria. The majority of these companies are in manufacturing, services, trade, construction and real estate. They are described as mostly profitable and agile — and quick to adapt to new opportunities. More importantly, of the Chinese companies surveyed by McKinsey, 89% had local employees, translating into 300 000 jobs for African workers. This suggests that Chinese-owned businesses may employ several million Africans across the continent.

Hisense, for example, announced in September 2020 that it would be opening a new electronics factory in Atlantis, north of Cape Town. This will be the company’s second factory in the area, employing more than 200 people to make washing machines. Its first, opened in 2013, manufactures fridges and televisions. The company employs 800 people and exports to 13 other African countries.

The establishment of the AfCTFA is undoubtedly a good move for the continent. It will help African governments and companies to negotiate with the rest of the world, strengthening inter-African trade and giving companies bigger backing when it comes to exporting goods. It could potentially streamline operations and reduce opportunistic corruption at border posts. And most of the current focus of AfCTFA seems to be on the trade of food items and perishable products like meat and corn, which are not the main imports from China anyway.

Rather than worry about competition from China, it seems more helpful to look at how AfCTFA could help entrepreneurs and business owners in Africa — including the Chinese-owned companies — to create more jobs as well as products and services. It is estimated that small and medium businesses (SMEs) in South Africa represent 98% of companies. They also provide jobs for up to 60% of the local workforce. Investment in SA has dropped over recent years and the political climate in the country, coupled with the lack of development on structural reforms, is giving many cause for concern. Civil service incompetence and political maneuvering are not conducive to a climate of economic growth and development.

This explains why business confidence was at an all-time low in South Africa in 2020. When we talk about the potential success of AfCTFA, more needs to be said about improving business and entrepreneurial conditions for local and other business owners. This should begin with cutting through the red tape for anyone wanting to set up shop. For some, it can take years to get a mining licence or to have working visas approved. Improving business opportunities for entrepreneurs could be the best way of giving the AfCTFA a real shot at becoming a powerful economic global trading partner and the African economic success story we all want.

Dr Steven Kuo is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer at the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business (UCT GSB), one of three Triple-crown accredited African business schools.