Annika Surmeier is a senior lecturer at the UCT GSB. She co-authored this article with Addishu Lashitew and Tenner Methvin. This article first appeared in Brookings.

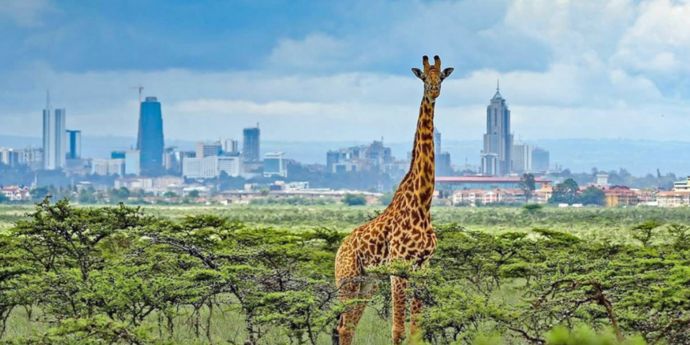

More than half of Africa’s 1.3 billion people make a living from agriculture, of whom 80% are low-income smallholder farmers working on farms smaller than two hectares.Significantly reducing poverty requires substantial improvements in the productive capacity and market access of millions of smallholder farmers in Africa.

In recent years, large food and beverage companies have introduced initiatives that integrate smallholder farmers into their value chains. These efforts are driven by the goals of increasing quality raw material supply, diversifying geographic risk, and empowering smallholder farmers economically and socially.

Heineken, a Dutch brewery, has launched a supply chain project in Ethiopia to increase local sourcing of malt barley in its breweries. The project has provided agronomic training, farming inputs, and market access to more than 40,000 smallholder farmers. These interventions helped double farm yields, leading to an estimated USD 59 million incremental increase in farmer revenues.2

Nando’s, a South African casual dining chain, has successfully developed a smallholder farmer value chain for one of its key ingredients, peri-peri chili. For ten years now, the initiative has reached thousands of farmers in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Mozambique, supplying 100% of its peri-peri demand. Currently, the project includes 724 farmers who earn an average income of USD 955 per year—significantly greater than income earned from alternative crops.3

How to develop inclusive value chains that create impact for smallholder farmers

Integrating smallholders into large value chains can be difficult. The successful experience of Heineken and Nando’s, however, provides valuable insights on how to create truly “inclusive” value chains. The following three insights are particularly relevant.

1. Ensure that inclusive value chain initiatives contribute to strategic objectives

Building inclusive value chains is complex and time-consuming. Such initiatives are more likely to enjoy sustained corporate-wide backing when they are aligned with strategic objectives.

A critical factor behind the success of the Nando’s project was its focus on securing a safe and reliable supply of peri-peri chili, which is deeply intertwined with the company’s history and brand identity. By sourcing peri-peri from African farmers, Nando’s was able to build connections between its global workforce and African roots. This enabled the initiative to garner sustained support from the company’s procurement, marketing, and HR teams in the face of multifaceted challenges.

Heineken was motivated by the desire to develop a reliable supply of local malt while meaningfully contributing to local economic development. This created ample commitment for investing in a complex initiative that has lasted several years.

2. Partner with organizations with distinct expertise and context-relevant knowledge

Both Heineken and Nando’s collaborated with different partner organizations, selected for their specialized expertise and context-relevant knowledge. Heineken worked closely with local consultancy firms and microfinance institutions to understand the needs of farmers and provide them with credit services. Nando’s maintained an intense collaboration with Impact Amplifier—a consultancy specializing in social impact—and several implementing partners in Malawi, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe that provided agronomy training, aggregated chili harvests, and coordinated post-harvest processes.4

3. Devise solutions that reduce transaction costs in the value chain

Smallholder farmers are often considered ill-suited for industrial-scale procurement because they lack robust quality controls and can be more expensive than commercial farmers due to production and distributional inefficiencies. Nando’s addressed these issues by picking a crop that is labor-intensive, which allowed smallholder farmers to compete on price with commercial farms. By using local partners to aggregate peri-peri chili, manage post-harvest handling, and introduce traceability controls, they streamlined quality control and eliminated logistical inefficiencies. Likewise, Heineken worked closely with the International Finance Corporation to provide training with the aim of developing the agronomy and business skills of its partners. These programs reached dozens of farmer intermediaries (farmers’ unions and cooperatives) who aggregated inputs and outputs across thousands of smallholder farmers.

Conclusion

The experiences of Heineken and Nando’s demonstrate that inclusive value chains, while not a panacea, can go a long way toward improving the living standards of impoverished farmers. Designing inclusive value chains requires changing corporate systems, which takes commitment, time, and experience. It also requires sustained partnerships to develop new capabilities, secure local support, and build trust. To create inclusive value chains that truly benefit smallholder farmers, companies need the willingness to challenge themselves, to develop new capabilities, and to reevaluate how they define value.