Freedom Day celebrations ring hollow when the vast majority of black people in this country remain economically and socially marginalised. To unlock our future, we must invest in our people — and fast — to build a new culture of innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking.

When South Africa attained independence in 1994, euphoria swept across the country and expectations were high. The democratic order that was ushered in was expected to create stability and jobs and eradicate poverty and inequality. It was meant to mark the end of socio-economic and political injustice. But as is all too clear today, this has failed to materialise.

Despite buoyant economic growth—averaging almost 4% between 1994 and 2007—accompanied by prudent fiscal and monetary policy, inequality and poverty have got worse since 1994 and according to a 2018 World Bank report, race still affects people’s ability to find a job.

There have been some successes in the delivery of social and physical infrastructure, but in the main, the introduction of specific policies meant to give previously disadvantaged groups a leg up, such as Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) legislation, have failed, with mainly the elite and the politically connected benefitting. Most black South Africans remain side-lined from the mainstream economy—hamstrung by a lack of access to capital, land, skills, and product knowledge.

This, in turn, has created social instability. The credit rating agency, Moody’s Investors Service, warned in 2019 that high inequality tends to be associated with higher levels of corruption and weaker government institutions — factors that can undermine overall institutional strength.

And all of this is likely to get worse as COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc across the globe, hitting developing countries, such as South Africa, hardest.

Tapping into the country’s innovative potential is key

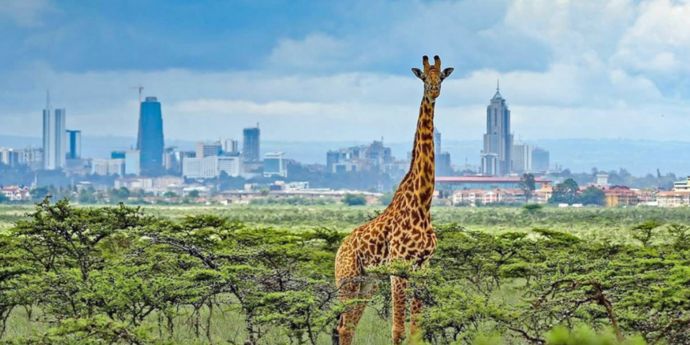

With growth and, as a consequence, new job prospects dwindling, SA needs to urgently reorient the country away from the minerals and energy complex (MEC). As Fine & Rustomjee have eloquently argued, the MEC has retarded South African industrialisation. Moreover, it is increasingly acknowledged by scholars that growth through harnessing natural resource rents is volatile and transitory, oriented towards growth-damaging rent-seeking behaviour, and discouraging investment in human capital. Additionally, with its increasing population, SA’s natural resource wealth per capita is declining anyway, so it is not even clear that the MEC is a viable strategy.

Instead of chasing shadows and pursuing development through a path that has failed over the last 50 years, the country may have to shift its strategic direction and adopt entrepreneurial orientation (EO), i.e., innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking, as its new strategic posture. It is increasingly recognised that know-how associated with the generation and exploitation of knowledge is critical for economic growth for both rich and poor countries. Importantly, scholars highlight the significance of strategic entrepreneurship in diffusing this know-how and fostering transformative economic growth that can reduce poverty. In fact, in scholarly work I have done with Kalu Ojah, we show that countries that rely on the strategic creation, appropriation, and, most importantly, the risky diffusion of new product knowledge, i.e., EO, grow faster and more sustainably than countries that rely on exogenous luck (natural resources).

Therefore, if a poor country like South Africa, wishes to foster economic growth and development, its firms will have to master new methods of production, introduce new goods and services and conquer new markets; that is, the production knowledge stock will have to be augmented. Yet we have been lacking in this regard—mining being a prime example here with techniques hardly evolving in recent years, potentially hampering productive capacity.

To change this, productivity-enhancing high growth entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial firms need to be encouraged and enabled to proactively appropriate technology they did not create, innovate, and take more risks to diffuse their newly acquired capabilities, especially in tradeable sectors. The opportunities right now, especially in the transition to a green economy, agriculture, mining, manufacturing, healthcare as well as in tradeable services, are significant.

But this is easier said than done as many large businesses that are the repositories of the countries’ human and financial capital base are risk-averse or are shifting funds offshore and cutting investment and innovation expenditures in SA. Moreover, with the dysfunctional, parasitic banking system seemingly focussed on loan sharking, and a small venture capital sector, high-growth entrepreneurs struggle to access funding. This is undoubtedly a key factor contributing to the low levels of EO and consequently, the low diffusion of new product knowledge in the country.

Improving the allocative ability of (1) the private sector and (2) the financial system, is therefore an important starting point. One way of doing this may be to accelerate transformation in boardrooms and C-suites of corporate SA. Perhaps, more diverse boards may see less risk and show higher commitment to SA, than the current leadership who seem to mistakenly deem developed Australia a better investment prospect than developing SA.

Another way may be to allow more specialist banks to operate and compete for clients taking on idiosyncratic risks by supporting industry niches. We currently have five or so major banks, but there is no reason why we cannot have at least 400-500 specialised banks. For instance, the US has over 5,000 commercial banks and savings institutions which are the foundation of the entrepreneurial spirit that exists in that country today.

Lastly, we may have to be more deliberate in supporting the development of a venture capital ecosystem that will allocate capital to risky productivity-enhancing investments, rather than say, focus on loan sharking as our banking system seems to be doing.

Repairing the foundations

However, all the funding and risk-taking in the world may not be enough if South Africans lack the basic foundations in education to set them up to be successful. In previous research, we have demonstrated that education is a robust predictor of EO, especially at the secondary school level. Therefore, it is fundamental for fostering entrepreneurship and establishing an inclusive economy. However, human capital is not merely education. So, the same applies to the healthcare system. Increasing access to quality health care has the potential to expand access to economic opportunities since healthier adults are better equipped to participate in the economy.

But, despite liberal spending on education and healthcare since 1994, these systems remain broadly dysfunctional. It is not an exaggeration to say that the apartheid Bantu education system, which deprived black people access to the same educational opportunities and resources enjoyed by their white peers, has not been completely dismantled.

A stronger focus on nutritional support may also help improve education outcomes. A hungry or malnourished child will always struggle to learn and progress through the system. So, while the government school nutrition programme that provides over nine million learners meals every day at school has somewhat helped alleviate hunger, its reach is still not far and wide and deep enough. The broader social security system needs to be overhauled with child welfare as a top priority.

It seems an obvious point, but a country’s strength is founded on its human capital, and the MEC strategy deliberately discouraged investment in human capital. For SA to successfully execute an EO strategy the developing people of South Africa will need all the help they can get to reach their full potential.

The government is running out of time to fix this. They have to implement key reforms to get the majority of black people out of poverty and build a much more inclusive and equal society at peace with itself. The euphoria we saw in 1994 is slowly fading and is being replaced by a sense of foreboding. Urgent action is required to halt the slide.

Dr Thanti Mthanti is a senior lecturer at the UCT GSB. He holds a Ph.D (Finance) and is also one of a handful of Professional Risk Manager (PRM™) charter holders in South Africa.