The global COVID-19 pandemic has set back developing countries especially, but it also offers an opportunity to rethink their development path. We spoke to the UCT GSB’s Dr Mundia Kabinga on the role of development finance in helping to get the economy back on its feet while also creating greater opportunities for marginalised groups — including the youth — to participate more fully in this going forward.

Can you start by explaining what development finance is, and how it differs from conventional financing?

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) are financial institutions that go where conventional lending and equity financing fears to tread. Whether global institutions like the World Bank or more continental focussed institutions such as the African Development Bank (AfDB) or the European Development Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), DFIs provide funding to public and private sector projects, economic sectors (like SMEs, and emergent industries such as digitization, artificial intelligence, and Fintech) or groups (like women or black entrepreneurs) not well serviced by the mainstream financial sector.

What sets DFIs apart from commercial banks is that while the likelihood of returns on a loan outweighs other considerations, DFIs also take into consideration factors like job creation, gender equality, youth employment, and the public good of diversifying the economy. DFIs essentially de-risk — or reduce the amount of risk — associated with projects directed towards such development goals through the provision of concessional funding, for example, loans, offered at below-market interest rates and/or over longer periods.

DFIs have been around for some time, and are as common in developed economies as they are in developing ones. America’s famed post-WW2 Marshall Plan, which underpinned the ‘miraculous’ economic recoveries of the likes of Germany and Japan, is considered an early blueprint. And there is increasing evidence to show that DFIs have a positive — although not always significant — impact on developing nations. Development finance has stimulated manufacturing in emerging markets, particularly the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore), led to improvements in human development, and has even made inroads into poverty reduction.

How significant a role has development finance played in Africa?

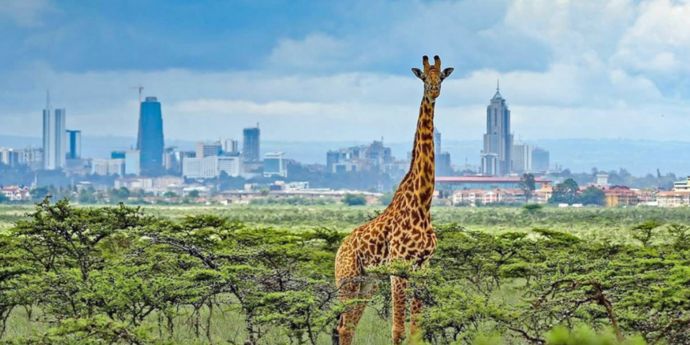

Development finance is key to achieving our development goals, and DFIs have contributed around US$500 billion in financing to Africa in over last decade. The World Bank Group has invested US$116 billion in sub-Saharan Africa in an assortment of grants, credits, loans and guarantees between 2011 and 2019; whereas the African Development Bank Group also mobilized US$115 billion in 2019 for investment in Africa; and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has pledged US$100 billion in Rapid COVID-19 Assistance Funds available for African countries to access in 2020. Other regional and national DFIs such as the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) and the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) to mention but a few, have also made sizable contributions to development financing in their respective countries.

In a 2019 report on impact investing, researchers — including those from the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business (UCT GSB) — were likewise upbeat about the role of DFIs and their “positive effect on the growth patterns of Africa”. Thanks to DFIs and others, investments are being directed to areas of pressing concern, including agriculture (thus food security) and social infrastructure like housing, healthcare and education. But despite the widespread availability of such funding, progress in Africa has generally been sluggish.

The global Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak is only intensifying the development challenges facing African countries. Is this a special opportunity for DFIs to step up to help build the economy?

The unfolding COVID-19 pandemic is indeed a humanitarian and economic tragedy that is exposing the massive inequalities in our society, but it could also herald a much-needed rethink of the transformative role of development finance in Africa.

A McKinsey report on the impact of COVID-19 in Africa, published in April, predicts that Africa’s economies could experience losses of between US$90 billion and US$200 billion on account of GDP contraction, and that the jobs and incomes of around 150 million Africans are likely to disappear during this crisis. The World Bank Group forecasts similar disruptions to economic activity world over.

Others like 2019 Nobel laureate economists Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo have echoed the call for a “COVID-19 Marshall Plan for poor countries”, drawing parallels to Europe and Asia, and describing pandemics as being similar to war bombings as “the levelling of the economy is mainly caused by external forces”. Even influential Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo, who in her 2009 book ‘Dead Aid’ lambasted foreign aid for fuelling corruption and poor governance in Africa, in a recent article in ‘The Economist’ argued that a “modern ‘Marshall Plan’ for Africa… could prevent a humanitarian tragedy and pay dividends for generations”.

But DFI funding could become more than mere bailout funding and can be deployed at this critical time to re-imagine and transform developing economies.

What might such a reimagination look like?

The post-apartheid economy in South Africa has largely been commodity-based and lacks diversity, with a weak manufacturing sector that quickly crumbled in the face of international competition. In a 2019 working paper, researchers from the University of Johannesburg argued DFIs here would need a coherent policy to drive the necessary industrialisation that could benefit the country in the long run.

Here we are talking in particular of the ‘other South Africa’ — borrowing from the term so famously used by Dr Martin Luther King Jr — meaning those marginalised groups who have borne the brunt of the economic lockdown, notably black women and the youth.

Where do the main opportunities lie post COVID-19 for our economy?

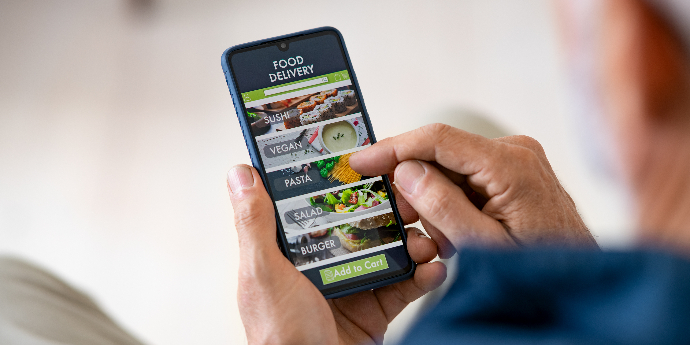

As the World Economic Forum pointed out in a recent article, this crisis is catalysing huge changes and few industries will avoid being either reformed, restructured or removed, so if ever there was a time to shift gears on development, it is now. Development finance must be channelled towards projects that not only promote inclusive development, but that take advantage of emerging megatrends and paradigm shifts in the post-COVID-19 world. Two notable examples of such shifts include the acceleration of digitisation and AI — to take advantage of shifting modes of consumption, supply, interaction and productivity caused by remote working — and supply chain localisation to guard against future disruptions caused by relying too heavily on a limited global supply chain.

This speaks to our own need for a strong manufacturing base, which in turn would then also help us to tackle unemployment, create training opportunities, and prepare us for the fourth industrial revolution.

Pandemics and other crises are cyclical. There will be more. We should use COVID-19 as a manual to build resilience and agility for the future.

Dr Mundia Kabinga is a development economist and senior research fellow at the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business (UCT GSB).