On 27 April each year South Africans celebrate Freedom Day in commemoration of the first democratic elections in 1994. We asked UCT GSB Professor Thomas Koelble to give us his thoughts on whether support for democracy in the country is waning, and how this system is being affected by globalisation.

Since its launch in March 2021, the Defend our Democracy campaign has had the backing of more than 300 leaders in the public and private sectors. Do you think South Africans are starting to lose hope in democracy as a means of delivering political and economic freedoms such as good governance, poverty reduction an employment?

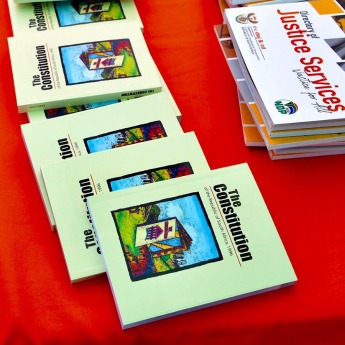

The Defend Our Democracy campaign is, at least partially, a response to the relentless attack by some politicians - Zuma is certainly not the only one - on the constitution and on the democratic procedures of government as a source of lack of transformation. This attack also aims to undermine the judiciary and any other state institution that stands in the way of a very broad coalition of interests who feel that the transition from apartheid to constitutional democracy did not bring about the desired socio-economic transformations that the liberation movement had hoped to achieve. What is also the case is that this coalition of interests includes a broad group of politicians, especially at municipal levels of governance, who exploited the lack of accountability and oversight institutions for the advancement of their own financial interests. The problem here is that the lack of transformation has become a defensive mechanism for groupings like RET to justify their actions - corruption in government is not corrupt if it furthers transformation. That this set of interests has broad support among the population is not surprising given that inequality has increased since 1990, people's standards of living have not improved much, the informal economy is arguably larger today than it was in the 1990's.

The political scientist Bo Rothstein, who heads the Quality of Government Institute at the University of Gothenburg, has convincingly argued that democracies are over-rated when it comes to providing legitimacy to governments and the state. People are affected much more by the output of government and the state, their policies and the bureaucracy that deals with citizens day-to-day issues, than by the input such as elections and the politicians that are elected. If there is a perception that public servants are untrustworthy and corrupt, citizens believe that the entire society is untrustworthy and corrupt. And that it is impossible for anyone who is trustworthy or honest to thrive. And the opposite applies - if public servants are seen as trustworthy and impartial, then citizens infer that the general society is trustworthy, impartial and that others will "do the right thing". Unfortunately none of the state institutions in SA enjoy high levels of trust in the wider society. This, of course, is rooted in the apartheid past because few people would have trusted the police or administrators to have their interests at heart. But as a democratic project, South Africa has failed - immensely - in turning around the perception that the state only serves certain privileged interests. While politicians have credibility and legitimacy, the state and its bureaucracy does not. And if the state fails to deliver basic sanitation, water, electricity, infrastructure, decent schools, housing, a modicum of personal security, welfare and health systems it cannot surprise us that people would rather forgo the right to vote if it means getting the basic necessities of life adequately organised.

One of the impacts of globalisation in developing countries is the rise of a dominant capitalist class with increased influence over government and public sector decision-makers. How much of a threat do you think globalisation is to democracy in Africa?

Democracy is a system of government that is based on the idea that "the people of a given and defined territory are sovereign". This idea assumes that there is such a thing as "a people"; that there is a legitimate claim to the territory of that particular set of "the people" (just think of the issues involved here in terms of claims to territory); that the people can articulate a political will; and that the people, not just individuals, are capable of making collective decisions (some politicians exploit this by claiming to speak for "the people"). In modern democratic systems, the basic idea is that "the people" elect representatives that speak for them. And that these representatives then develop ideas and policies as to how to best articulate what the people want. Now, this is quite a set of assumptions! We have endless debates about whether there is such a thing as a commonality called 'the people'; we have ferocious debates about who is to be included from the people and excluded; we debate the virtues of our 'representatives' and so on.

Democracy is based on a claim to sovereignty and what globalisation has done over the last 40 years or so is to erode the idea of sovereignty. The most obvious example is the globalisation of financial markets and in terms of trade regimes. One aspect of economic sovereignty is the control over the value of a country's currency. This sovereignty has long disappeared with the emergence of global financial markets. And there are many other issues where global rules and global institutions are questioning/undermining national policies, national interests and actions. Moreover, many countries are actually quite keen to push certain kinds of decisions away from the national to the supra-national level - we have organisations such as the United Nations, the African or European Union for precisely those reasons. Some issues cannot be dealt with only on the national level - take climate change for one. So, it is not so simple to answer this question because there are so many underlying assumptions and issues that need to be unpacked before we even begin to address the question of whether globalisation threatens democracy. It certainly brings into sharp relief the assumptions underlying the concepts of the "nation", the "people", "sovereignty" and "people's self-governance", which may all be imagined.

Judge Jody Kollapen is one of eight candidates recently interviewed by the Judicial Service Commission to fill two vacancies on the Constitutional Court. During his interview he is reported to have said that “in the transition to democracy, South Africans had perhaps focused too much on reconciliation and not enough on transformation.” He added that “reconciliation could not be achieved without transformation - without all South Africans accessing the economy.” What do you think of his assertion?

Kollapen's statement is a statement of the obvious. South Africa was socially, economically and politically engineered over 350 years of colonial and apartheid rule to the detriment of the African population and in the interests of the colonial and settler societies in the territory. The transformation in 1990 to 1994 was a negotiated settlement to bring about a democratic polity with a constitutional base. Less thought was given to how to address the many legacies of colonialism and apartheid, i.e. how to transform this malformed economy and society. Perhaps it was too much to ask at that point. Much was left to a vague notion of transformation of the state in the assumption that this ANC take-over would be sufficient to bring about the racial transformation progressive forces wanting to be achieved. And here we end up with the issue raised in question one about the nature of the state.

The economists Banerjee and Duflo in their latest book Economics for Hard Times argue that perhaps the best way to address the issue of transformation is to concentrate on the provision of good infrastructure, on providing as good of an educational sector as possible and to assist the population in terms of health care facilities. If the state does these things adequately, then a basis for broader growth is possible. If a population has access to electricity, water, sanitation, health care, education, housing and transport facilities, as well as adequate policing, the chances of being able to take the opportunity of upward mobility when economic growth returns is certain. If not, then the nasty politics of zero-sum economics remains and is likely to get worse. And that is where and when democracy fails - both fast and slow.

Thomas Koelble is a professor at the UCT GSB where he convenes the Business, Government and Society course which is designed to assist students in understanding the broader context within which businesses in emerging markets operate.