Q: In your article, “The 5 implications of COVID-19 for business leaders” published in 2020, you wrote, “Many scientists – and also an increasing number of business leaders – thus see COVID-19 as a tragic example of the broader risks to business and societies from our seeming inability to address environmental risks associated with climate change, biodiversity loss, and other “planetary boundaries.” Are there promising signs that the business community is making environmental sustainability a priority in the wake of the pandemic?

Yes, there are some positive signs of this happening. But as usual, the patterns are more complicated once you look at them in more detail.

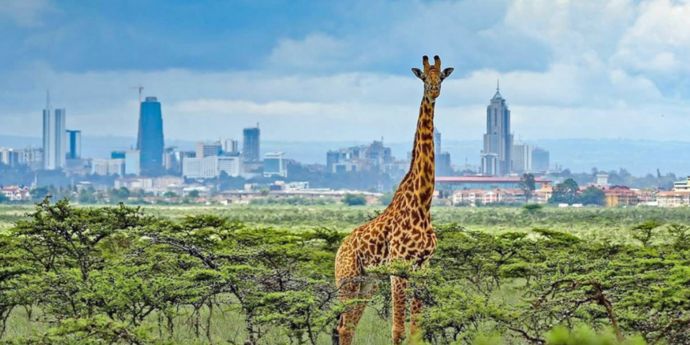

We recently completed an article (currently under review) exploring precisely this issue based on a comparative analysis of 25 companies in Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria, and South Africa. We found that in response to the pandemic, some companies have been restricting their sustainability strategies, while others have strengthened them. We identified three factors that combine to explain these differences, but arguably the most important is what we call the Covid-19 impact. That is, some companies have been affected more directly by the pandemic than others.

For example, tourism companies have had to shut down operations for some periods and this is obviously a very direct impact. On the other hand, some other companies have had little negative impact, or they have even benefited.

How do these differences affect companies’ sustainability strategies? We found that companies that have been severely impacted struggle to maintain their sustainability commitments, because they are trying to just stay afloat. On the other end of the spectrum, companies that have had little negative impact are more likely to continue with their pre-existing strategies, because there has been little incentive to really upgrade their sustainability efforts.

Hence, we found that companies with some intermediate level of Covid-19 impact were most likely to strengthen their sustainability strategies. The pandemic’s impact was severe enough to really jolt leaders out of their complacency, but it wasn’t so strong that it immobilised them. Interestingly, this applied to all companies – even those that had weak pre-crisis sustainability commitments. We call this leapfrogging.

Q: You have previously stated that business schools should play a much more proactive leadership role in responding to the climate crisis, and this view appears to be shared by the majority of the world’s leading business schools. According to AMBA & BGA’s International MBA Survey, just one fifth of employers think that Business Schools are producing leaders who make decisions that consider the environment, ‘a great deal’. What else should business schools be doing to lead the response to the climate crisis?

I think the pandemic has shaken up the business school landscape, as well. It has foregrounded the importance of companies’ social, political, and ecological context. I do think this will lead to changes in many business schools, in terms of what we teach and research. This is especially so because in parallel to the pandemic, the signs of climate change are becoming ever-more evident. This will be another record year as far as heat and storms go. The WMO has called this a “make-or-break year” with regard to climate action. The investor community is also undergoing a remarkable shift towards cleaner energy. Business schools that do not recognise the need for and depth of this shift, risk going the way of recalcitrant fossil fuel companies. Thankfully, some of these changes are bring increasingly driven by our students. I’ve been really impressed and energised by the knowledge, creativity, and inspiration that our students are bringing into our classrooms on our grand challenges of climate change and inequality.

Q: How do you believe the social justice issues exacerbated by COVID-19 should shape our future social and environmental policies?

It’s become common cause that the pandemic has both highlighted and exacerbated social inequality. I think it has also shown that high degrees of inequality can diminish societies’ resilience during a crisis. Such inequalities probably make countries more susceptible to the kind of silly populism we’ve seen in Brazil and the USA. Also, countries with effective policies to address inequalities have benefited from them during the pandemic. For example, in countries where employees have rights such as sick leave and so on, workers were more likely to stay home if they weren’t feeling well, which helped slow the spread of the virus. I like the term “social immune system” to point to this kind of society-wide resilience. I think that this lesson has sunk in, at least in some places. I suppose the difficulty is in finding the right balance between fiscal responsibility and welfare policies, such as a basic income, which deserve more careful consideration – especially in places like South Africa with such brutal levels of structural unemployment. I am not an expert in welfare policies, but I think that there may be an argument for such a basic income that combines moral reasons with value-for-money considerations for taxpayers.

My points above focus on governments and public policy, but similar arguments pertain to managers. It’s been interesting to see how many companies have really foregrounded employee wellness and a concern for their workers, as a response to the pandemic. It’s possible that the pandemic is foregrounding for managers, not only their companies’ interdependence with their social and political context, but also with their employees, with a possible shift at least in some places towards more relationship-based interactions, rather than just instrumental, contractual ones.

Ralph Hamann is a professor at the UCT GSB, working on business strategy and sustainability, collaborative governance, social entrepreneurship and innovation. He is an executive editor of "Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development", and co-founder of the South African leg of the Embedding Project and the Southern Africa Food Lab, two award-winning initiatives bridging research and practice.