In 2003, Thabo Mbeki – then president of South Africa – described South Africa’s economy as being like a two-storey house. The top floor was quite plush, with all the fittings packed neatly together. He referred to this as the modern, diversified economy within South Africa. Below that level, however, was an informal economy where the poor were trapped in poverty, with little or no skills. President Mbeki’s analogy went further: there was no interconnecting staircase between the two floors. In effect, South Africa had two economies and there was no bridge between them.

Since then, South Africa has built on the existing two-storey infrastructure without paying much attention to a stairway. At least, not one wide or sturdy enough to encourage upward movement. This poses a serious developmental problem; one shared by many developing economies in Africa. Academic research typically labels this as being a function of dualism and the lack of institutional connections between these dual economies: although institutions establish the ‘rules of the game’ governing economic activity in each of these economies, the institutions do not bridge the two disparate economies and so they coexist but in isolation. How often do we hear the refrain that big business does not do business with small business?

The result of this missing link is that the two economies struggle to engage with each other, leading to inefficiencies and substantial lost opportunities. Worse still, it entrenches social and economic divisions, and deepens inequality. We see this manifest in various ways in South Africa. Our deep and liquid financial markets, together with a highly functioning and well-regulated banking industry, means our top-floor financial system measures well against any of the leading economies around the world. Access to capital should therefore be widely available. But it’s not. Swathes of small businesses fail to meet the criteria set for top-floor financing.

How can this be fixed? Claiming ‘it’s the government’s job’ ignores other players who have the ability to play a more innovative intermediary role.

Stairway intermediaries open access to formal markets

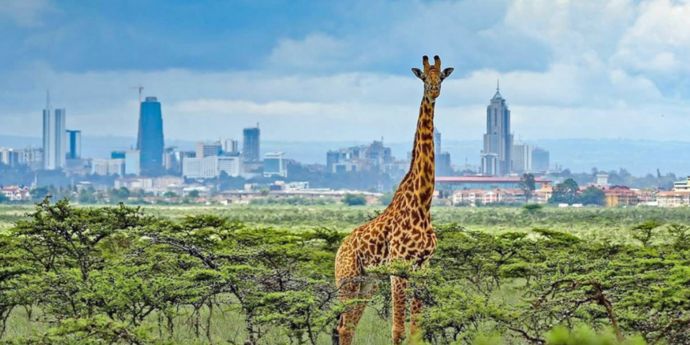

If South Africa’s two-storey economy is pronounced, Zimbabwe’s is severe. Its house is pyramid shaped. Yet there are attempts underway to connect the different levels. As part of the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business’ (UCT GSB) broader mission of focusing on sustainable impact in African business and society, Baldwin Guchu and I recently conducted research on the role intermediaries are playing in connecting Zimbabwe’s formal and informal economies. South Africa can learn from this.

Zimbabwe has a reputation for weak and extractive political and economic institutions. The World Bank estimates that the informal economy makes up approximately 60% of the total economy; roughly 90% of those considered ‘employed’ work in the informal economy. This is especially true in the agriculture space, where the combined legacy of colonialism and more recently, land grabs, has carved a chasm between large-scale commercial farmers and small-scale, often subsistence farmers.

These smaller agriculture producers cooperate in their villages through a system of mutual trust, but this way of doing things does not extend beyond the villages. Tight legal contracts are needed to sell to the bigger retail industry players. Furthermore, small-scale farmers need some level of financing to ensure access to machinery, and a sustainable supply of input commodities necessary to plant, harvest, and store their crops. This is impossible without collateral to guarantee a loan, or without buying contracts from retailers. Hence, they are trapped in a vicious cycle – neither able to borrow money to produce, nor able to produce to borrow money.

That’s where an organisation like Palladium steps in. They’re a private, for-profit entity that employs collaborative models and systemic approaches at the intersection of commercial growth and social progress to further market development. In this case through a donor funded project. Effectively, Palladium acts as a bridge between the formal and informal economies connecting small-scale farmers to formal markets – the staircase between the two floors.

Palladium functions as an intermediary through various interventions. It facilitates contract farming by connecting input suppliers with small-scale farmers, who then agree to sell the produce back to them at a pre-agreed future price. This addresses input financing and provides a guaranteed market for the farmers’ output. It also builds partnerships with the private sector to enable mobile buying systems. This frees farmers from having to find a market, and ensures them a fair price; furthermore, it relieves them of the problem of storage and packaging. As part of a consignment stock initiative, the intermediary also keeps an electronic transaction history farmers can use to access credit in the future by providing records and information that would otherwise be missing.

Longer-term, sustainable solutions are needed too

All these interventions are better served by intermediaries than bureaucratic government overreach, especially where government institutional capacity is weak and corruption is common.

Governments with little or no entrepreneurial mindset fail at this task because they don’t see a gap they can fill in a sustainable manner. What governments can do is enable policies that better support these intermediaries to function effectively, and to recognise that the traditional boundaries between the public and private sectors are increasingly blurred and hybrid partnerships provide the potential for innovative solutions. Big business needs to realise that maintaining the status quo of dual economies delegitimizes markets and results in lost opportunities.

The question for intermediaries is to imagine ways in which bridging support can extend beyond project initiatives. These projects are time-bound, with limited budgets. If not implemented with longevity in mind, such interventions can create dependencies rather than solve them. Hence, longer-term, more sustainable solutions must be imagined, not only to bring the formal and informal economies closer together, but also ensure permanent integration.

If we don’t enable and support intermediaries in South Africa, we will forever have a two-storey house with no stairway, leaving the majority stranded on the ground floor, looking upwards. With such structural inequality, the possibility for the whole edifice to come crumbling down looms large.

John Luiz is a professor at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business and the University of Sussex Business School.