For every headline making a powerful case for how technology can set Africa on the right development pathway, another will just as convincingly outline the underlying reasons why that promise will remain largely unrealised.

The United Nations, for instance, has been a perennial optimist regarding “the bright promises” of the digital revolution for Africa, persistently espousing digitalisation as “one of the most powerful tools for implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Africa’s Agenda 2063”. But even that bullish organisation has had to acknowledge that Africa has often squandered its opportunities. Many countries on the continent, for example, failed to capitalise on the digital acceleration during the COVID-19-associated lockdowns.

South Africa, it has been pointed out, is one of those countries that failed to leverage the unanticipated migration from the physical to the online worlds during the pandemic. That failure is largely because of the persistent digital divide in the country. The education of millions of disadvantaged children came to an abrupt halt, for instance, when they couldn’t turn to the internet and tech to continue their classes. Many businesses too, struggled to pivot fast enough and expand beyond their established markets into the digital space. These lost opportunities are the consequence of a failure of policy and infrastructure, compounded by pervasive poverty , inequality, and the like.

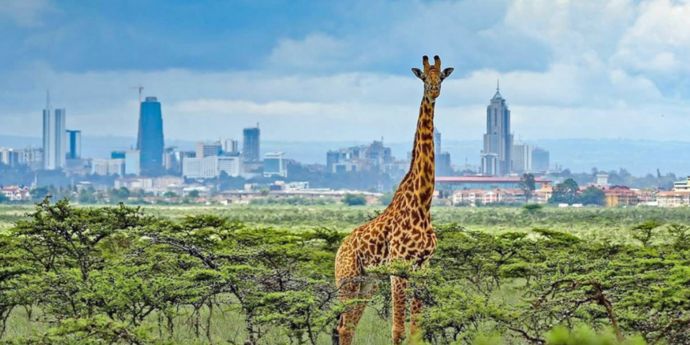

But that does not mean that there isn’t untapped potential for Africa to harness technology to further the human project on the continent, specifically using technology in the service of humanity by addressing social and economic challenges. Although there are significant hurdles that the continent needs to clear to unlock this potential.

The World in 2013: ICT Facts and Figures estimated that, on average, 31% of the population in the developing world was online, compared to 77% in the developed world. And that while half of Asia and the Pacific have access to the internet, the penetration rate in Africa stands at about 16%. These are substantial deficits.

Fortunately, part of the groundwork has been laid. The World Bank Group in 2019 suggested that internet access in Africa had climbed to 27%. Mobile technologies on their own are said to have already generated 1.7 million jobs and contribute US$144 billion to the combined continental economy, or a not-to-be-sneezed at 8.5% of GDP. By one estimate, some 615 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa will, by 2025, have subscribed to a mobile service, amounting to half the population in the region. That’s up from 495 million by the end of 2020, or 46% of the region’s population. The estimate also suggests that mobile technologies and services will add economic value to the tune of US$155 billion by 2025.

The real question is how do we build on this momentum? This is a question that continues to perplex especially businesses from outside of Africa, eager to gain a foothold on the continent.

- A good place to start is by understanding that the environment and context of business in Africa has its own unique flavour.

As the title of one book suggested, a kind of frontier mindset is generally required in the tech world, but in Africa, you need to also bring a willingness to learn, innovate and adapt. Tech businesses need to understand that “the map is not the territory”, and you have to immerse yourself in your market to understand how to create real value. This will ring familiar to those from the Executive MBA programme at the UCT Graduate School of Business where this approach is endorsed. At JUMO for instance, we make sure to put eyes and feet on the ground in our new locations, including our own and local teams. This process also helps us to understand how transferrable a business model is from one country to the next, and to come up with context sensitive and adaptive technological solutions to problems.

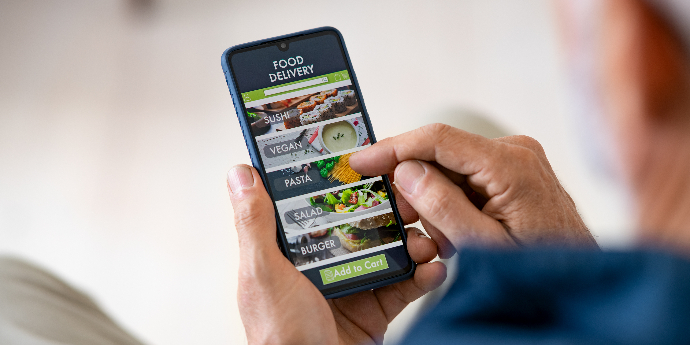

- Additionally, tech businesses need to be prepared to design for the lives that their customers actually live and lean into the kinds of numbers that scare them.

One example is a logistics company called LifeBank that developed a medical-supply delivery system in Nigeria. Founder, Nigerian-American Temie Giwa-Tubosun, had discovered that hospitals in the country were dumping vast amounts of blood simply because it wasn’t getting to them in time. LifeBank developed the necessary data-rich analytics and apps, and used everything from motorbikes to drones to make sure the blood gets to hospitals. This creative business model innovation has made a big dent into major issues such as maternal mortality. In 2019, Ms Giwa-Tubosun was awarded the US$250,000 African Netpreneur Prize.

- And finally, tech businesses need to be prepared to go with others and go with intentionality.

To be successful you have to build local partnerships, but remember to put well-thought-through agreements in place. In addition, intentionality matters as it is very easy to fall into the trap of thinking that technology is an answer on its own. Instead, businesses need to have very clear destinations and principles in mind.

Ultimately, our collective goal must be to use technology as a means to provide connectivity and useful services to as many Africans as possible. This will be good for the continent and its people and good for business too. And as long as there are people being excluded from technology, from basic services, from accessing finance, from decent healthcare and from the economy, we are creating an unstable environment in which businesses won’t be able to operate in the long run.

In a very real way, we are all in this together. And as long as businesses understand and act on this, then the optimists’ view of the continent is more likely to prevail.

Buhle Goslar is Africa CEO at JUMO, a mobile financial services platform for e-money operators and banks, directed at emerging markets. In 2019, she was named as one of South Africa’s Inspiring Fifty Women in Technology. She is also the 2021 Accion Claugus Award Winner for Advancing Financial Inclusion.