We live in an age of ubiquitous technology, from mobile phones to AI and cryptocurrencies — and yet there are still about one billion people across the globe who have no access to basic medical care simply because they live in remote regions.

Imagine you have a two-year-old who wakes up one day with a fever and you realise that she could have malaria, and you know that the only way to get her the medicine she needs is to get into a canoe, paddle to the other side of the river and then walk for up to two days through the forest just to reach the nearest clinic? According to Dr. Raj Punjabi, a Harvard Medical School Assistant Professor, who founded Last Mile Health in Liberia over a decade ago, this is the reality for far too many people in the world today. “Nobody should die because they live too far away from a doctor,” he says, especially in this age of modern technology where mobile phones in particular offer us a solution.

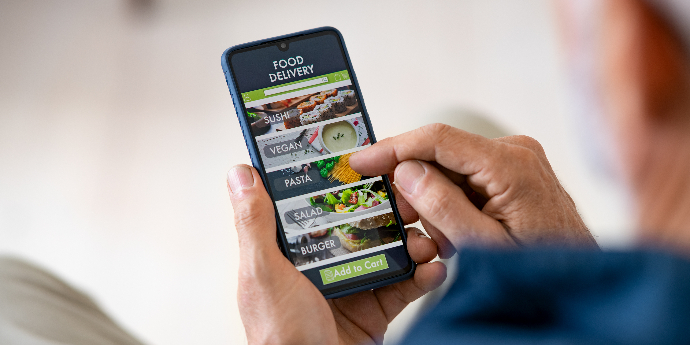

Smartphone technology has improved access to life-saving treatment

In 2017, 44% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa had mobile phones. Their rapid spread has defied expectations and Last Mile Health is turning this fact to Africa’s advantage. In partnership with the Liberian government, it trains Community Health Workers (CHWs) to prevent, diagnose and treat a whole range of medical conditions and diseases; using smartphone technology and apps to help thousands of people in rural areas. Their interventions have seen the rate of children getting life-saving treatments increasing by 50% in some areas. CHWs are able to treat common medical problems like malaria and pneumonia, and can dispense medication and test for a range of diseases through use of innovative medical devices like Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs).

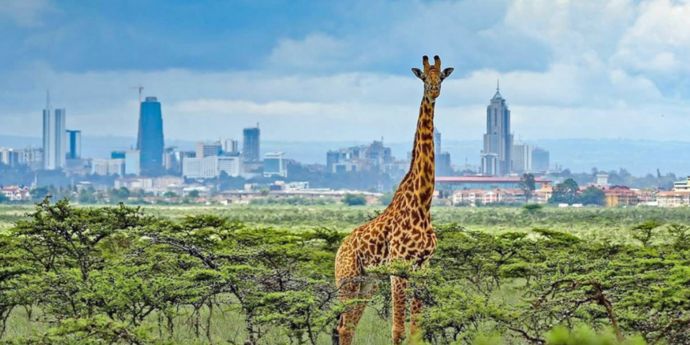

Last Mile Health is one of several healthcare innovators in Africa that are using mHealth (shorthand for mobile health) technology to reach rural communities with similar results. Living Goods in Kenya recruits people on a micro-entrepreneurship model to sell goods like mosquito nets, solar lighting and nappies door-to-door. Having gained access to homes, the entrepreneurs are then able to provide contraception, sell medication and carry out health assessments on a mobile phone they are equipped with — which then links to the government health system. VillageReach in Mozambique meanwhile has developed a proactive model that works to create an enabling context and connect key players — including mobile service providers — to enable healthcare delivery in that last mile.

Sharing best practice to collaborate and scale

Imagine the power and potential if these organisations were able to link up and share best practice to collaborate and scale their success? This is precisely what the Health Systems Entrepreneurship (HSE) project, a two-year initiative run by the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the UCT Graduate School of Business (GSB) and funded by Johnson & Johnson- set out to achieve, with startling results.

This project came out of the Social Innovation in Health Initiative (SIHI), hosted at TDR, the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, and was conceived as an opportunity to better understand how social innovators in health integrate their solutions with government.

When government buys in — as it has in Liberia, where Last Mile Health helped to develop curriculum and training modules for all government CHWs — the impact of the innovation is wider and more sustainable.

“Success often depends on an organisation’s ability to support governments as [the latter] assume responsibility for and eventually own a programme’s ongoing operations and management. If it can’t, the solution and its positive impact on the community can disappear or require external funding in perpetuity,” write the VillageReach team in a recent SSIR article.

But not all organisations have the time and resources or the knowledge and skills needed to achieve this outcome.

The Health Systems Entrepreneurship project set out to change this by connecting six SIHI identified projects including Last Mile Health in Liberia, Living Goods in Kenya, Muso in Mali, the Inhangane Project in Rwanda, VillageReach in Mozambique and mothers2mothers in South Africa to promote collaboration for inter-organisational and government integration.

While all the organisations knew of each other, they mostly did not have the time or the resources to learn from each other in any meaningful way. Through the simple opportunities we created, which included funded visits to one another; the scheduling of regular conference calls for peer-to-peer learning; as well as seminars and workshops — they were able to share best practice, with many reporting that the opportunity to use each other as a peer sounding board was particularly valuable.

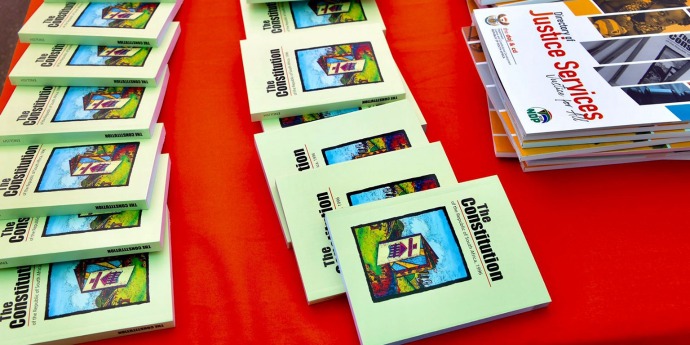

A framework for transitioning social solutions to government ownership

One of the tangible outcomes from this collaboration has been the development and publishing of a framework on how to transition social solutions to government ownership. Piloted by VillageReach, using material gained through our workshops and “pressure tested” with peers in the cohort, this innovative document lays out a clear pathway for non-profit and private-sector organisations who want to transfer the implementation of their solutions to government agencies.

The overwhelming learning from the Health Systems Entrepreneurship project is that no one organisation, no matter how innovative, can do this work alone. Creating successful health outcomes is complex and is critically dependent on building enduring relationships with other actors in the health ecosystem, including local health systems and community members. There are many obstacles around bureaucracy, administration and communication that need to be overcome. This takes time and ongoing effort, but the rewards for persevering are significant.

The potential to empower and upskill many more millions of people on the frontlines of healthcare in rural areas is real — and it doesn’t require a radical new technology solution, but rather radical collaboration and the commitment to reconfiguring the assets that are already in the system for better outcomes.

As funders and academics, we believe that one of the best things we can do to support this process is to continue to find ways to connect frontline health initiatives like the six in our first cohort - to enable them to collaborate and learn from one another and so create more efficient and effective healthcare systems. The measure of our collective success should be that in the future, parents don’t have to journey for two days with a sick child to reach help. After all, as Dr. Punjabi says, “We are not defined by our conditions no matter how hopeless they are, we are defined by how we respond to them.”

Katusha de Villiers is the acting senior manager of the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship, and the senior project manager for the Bertha Centre’s Health Systems Entrepreneurship (HSE) project.