While government has identified DFIs as a key partner in delivering an economic turnaround — these institutions lack capacity and resources to do their jobs effectively. Fixing this will be a necessity.

In his maiden medium term budget policy statement presented in Parliament in October, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni emphasised that increased investment in social and economic infrastructure will be a key focus of SA’s economic recovery strategy over the medium term.

Government, said Mboweni, will develop a framework to help investors assess potential long-term returns on public infrastructure projects.

“We want to enable investment in public infrastructure by commercial banks, development finance institutions and pension funds,” the Minister said. Over the next three years, public infrastructure expenditure is estimated to amount to just over R855bn, of which state-owned companies account for about R370bn, and general government the remainder, mainly in the form of conditional infrastructure grants.

However, with government struggling to meet its revenue collection targets amid weak economic growth, the role of Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) in financing infrastructure projects will be particularly important in the drive to kickstart SA’s ailing economy.

Infrastructure a strong foundation

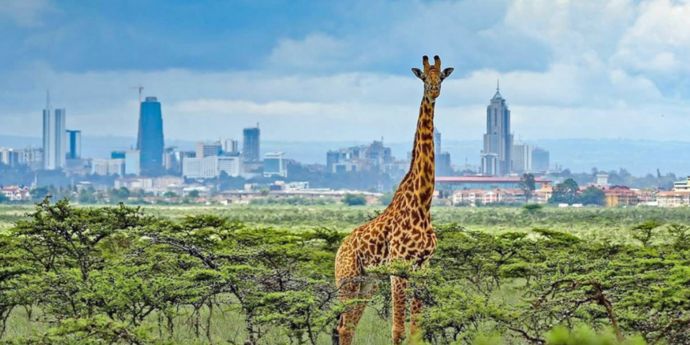

Infrastructure development is often cited as the foundation on which to build a strong economy. The East Asian "Tiger" economies, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, offer a pertinent case study of how infrastructure can be a catalyst for economic growth. The rise of their economies largely hinged on manufacturing, health, agriculture, energy, education, and indeed infrastructure.

The World Bank highlighted that starting in the 1960s, the “Tigers” began attracting foreign direct investment with government support that allowed an accumulation of capital that led to a growing capital to labour ratio that favoured manufacturing. Their labour intensive exports of consumer goods targeted highly developed nations. This reduced their demand for imports through measures such as tariffs, which ensured a positive balance of payments. They then reinvested the funds into infrastructure and human capital that produced human capital dividends. Since then, the Asian Tigers have become leading economies.

The South African government is therefore on the right track by emphasising on infrastructure led growth, and at the same time focusing on improving health care and the education system as articulated in the National Development Plan, government’s blueprint for development. As part of the much talked about stimulus package, a public-private infrastructure fund is being established within the Presidency in a bid attract private and development-finance capital to public infrastructure projects.

What exactly is a DFI?

DFIs aim to have a developmental impact in the markets in which they invest, alongside the requirement for sustainable returns. They are typically majority-owned by national governments and source their capital from national or international development funds or benefit from government guarantees.

According to José de Luna MartÃnez a lead financial sector specialist at the World Bank Group, historically, DFIs have been created by governments around the world to promote economic growth and support social development. They typically provide credit and a wide range of capacity-building programs to households, SMEs, and even larger private corporations whose financial needs are not sufficiently served by private banks or local capital markets. In doing so, they seek to promote strategic sectors of the economy, such as agriculture, international trade, housing, tourism, infrastructure, and green industries, among other sectors, states MartÃnez.

Some of the major international DFIs investing in Africa include the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the European Investment Bank (EIB). There are also several African DFIs, the largest of which is the African Development Bank. The Development Bank of Southern Africa has also played a key role in many developmental projects in SA and sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. The New Development Bank (NDB), also referred to as the BRICS Development Bank, is another prominent and more recent player.

Underperforming assets

However, despite some successes here and there, DFIs have to date largely been ineffective in achieving development on the continent, in part because they lack capacity.

To unlock the potential of DFIs, the institutions must be overhauled and better resourced. As Erastus Mwencha, the former deputy chairperson of the African Union Commission (AUC) states: “there is an imperative to revisit the role of African Development Finance Institutions with a view to reinforce their development potential and address their poor performance recorded over the last decade.”

Mwencha argues that governments should put in place arrangements for DFIs to be assessed on a regular basis against an agreed set of financial and social development objectives. There is a need for clear and focused mandates, robust corporate governance standards, acceptable level of government control, appropriate lending and risk management technologies, and the ability to recruit and retain qualified staff. As one analyst points out: “A growing body of empirical evidence indicates that once DFIs are provided with strong governance structures and the right incentives they can play an effective role in expanding financial access, ultimately contributing to economic and social development.”

It is also necessary to invest in the production and publication of good research related to development finance in order to understand better how to improve their efficiency. Despite a growing literature looking at the impact of individual investments and projects on development, gaps still remain in the research of both the micro and the macro impact of DFIs and indeed their inner workings. What is also lacking is the relevant professional capacity in development finance, there is an urgent need for more skilled individuals who can work in the sector and improve the functioning of DFIs.

If managed properly, DFIs can be central in the development of the continent. If local DFIs can be sufficiently capacitated to perform optimally, SA and the rest of the continent will no doubt take a major step forward and possibly catch up with other developed economies such as those of the East Asian Tigers.

Professor Nicholas Biekpe is the director of the Development Finance Centre and convenor of the MCom in Development Finance at the UCT Graduate School of Business.