The impact of energy on an economy has been dramatically illustrated in South Africa in recent months following a spate of load shedding — reportedly costing in the region of R2bn a day. The energy crisis, including the problems at Eskom, has further dampened investor confidence in the country at a time when the government urgently needs foreign capital, amid ballooning debt and an unsustainable budget deficit.

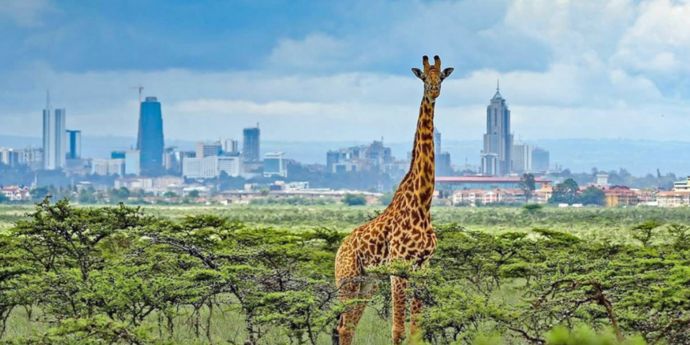

Hard to believe under such circumstances, that SA is one of the lucky ones. Power shortages and blackouts are routine in the majority of African nations. Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding SA) has the lowest electrification rate in the world, with up to 60% of the population still without access to electricity.

The World Bank highlights that the entire installed generation capacity of Africa’s 48 Sub-Saharan countries is less than that of Spain or South Korea. As much as one-quarter of that capacity is unavailable because of aging plants and poor maintenance. And if we were to combine the power systems of all 46 sub-Saharan African countries (excluding SA), we would still end up with a power system smaller than that of SA.

Undoubtedly, the energy crisis has hampered the continent’s economic growth. Furthermore, as some observers point out: “The provision of power to a population is not simply an economic conversation, but rather a humanitarian one.”

If current access to energy trends continue, warns the World Bank, fewer than 40% of countries on the continent will reach universal access to electricity by 2050. The economic cost of power shortages can amount to more than 2% of gross domestic product. For some countries, it has shaved as much as one-quarter of a percentage point off annual per capita GDP growth rates.

In attempting to address this crisis, renewable energy inevitably emerges as a solution. Africa has better solar and wind resources than most other regions in the world. And, with the cost of renewable energy falling fast, it will be a consistently cheaper source of electricity generation than traditional fossil fuels by 2020, according to a new report from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Already, newly built solar and wind projects in countries such as India, Mexico, Chile, Morocco, Namibia and Zambia are being delivered at record-low coal-busting prices. And the results from SA’s latest round of renewables procurement supports this, with average prices at or below Eskom’s average cost of supply. New procurement rounds are likely to see bids at prices below the running costs of Eskom’s more expensive coal-fired power plants.

Even so, finding the resources to secure investment into renewable energy on the continent will be far from easy. According to the World Bank, the cost of addressing the needs of sub-Saharan Africa's power sector has been estimated at $40.8bn a year, which is equivalent to just over 6% of Africa's gross domestic product. Existing funding is far below what is needed and this yawning funding gap cannot be bridged by the public sector alone.

One way to achieve this is through public private partnerships and the use of innovative financing mechanisms such as project finance, which is emerging as a leading tool to finance infrastructure projects — especially in emerging economies. These complex financing structures usually involve multiple investors and lenders that are paid back from the cash flows generated by the project. The advantage of this approach is that it is able to alleviate investment risk and raise finance at a relatively low cost, to the benefit of investors and consumers alike.

There is good evidence that this approach is effective. The Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) recently received the African Renewable Energy Programme Award from Project Finance International (PFI), primarily because of the successful financial closure and implementation of several projects it financed in Round Four of South Africa’s world-renowned Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REI4P). Unfortunately, these kinds of specialised skills are in short supply in the region, suggesting the need for targeted interventions to address this backlog.

The SA Wind Energy Association (SAWEA) points out the REI4P has had a tremendously positive impact on the SA energy sector and economy — as well as delivering significant socio-economic benefits. To date, renewables have invested close to R202bn (24% of which is foreign direct investment) in SA and contributed 26 840 GWh to the national grid. And new research from the CSIR also indicates that renewable generation capacity has played a key role in recent months in keeping load shedding from being worse than it was.

South Africans own, on average, 48% equity in all IPPs while black South Africans own on average 31%. Perhaps more significantly, the sector has created about 38 700 job years and has the potential to create more if it is given the support it needs to realise its full potential.

SA’s REI4P programme has proven that it is possible to deliver world-class built power projects on time and within budget and this knowledge can be rolled out to the rest of the continent. It is within our grasp to secure the generation of affordable, sustainable and reliable power in Africa. It is now up to the politicians and the broader investment community to work together to ensure that Africans get the power future they deserve.

Wikus Kruger is a University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business junior research fellow & PhD candidate. He coordinates the Finance, Contracts And Risk Mitigation For Private Power Investment In Africa programme.