As African countries scramble to acquire and roll-out vaccines across the continent, the urgent need for reliable energy supply is once again in the spotlight.

Health officials say at least two-thirds of Africa's 1.3 billion people will need to be vaccinated against COVID-19 if the continent is to achieve herd immunity. Meeting this target will be difficult, not least because of the lack of reliable power supply.

Most of the COVID-19 vaccines require stable ultralow (-70 to -5 degrees Celsius) to low (2 — 8 degrees Celsius) temperatures to maintain their viability. The lack of energy security across the continent is consequently slowing down the vaccine rollout, which could potentially lead to more deaths, and slower economic recovery.

According to a report by Reuters, even in African countries where the relevant equipment is available, power and personnel may not be. In nations as different as Nigeria, South Sudan and Zambia, for example, electricity supply is extremely unreliable and most of the population remain disconnected from the national grid. Many hospitals consequently depend on diesel-powered generators, but often can’t afford refuelling and maintenance — putting patients requiring life-saving machines such as ventilators in danger. A 2014 World Health Organisation study found that only around 28% of health facilities and 34% of hospitals on the continent had access to reliable electricity. This is not sustainable.

The African Development Bank has previously highlighted that just one person in five has access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet sector and regulatory reforms that could unlock investment remain painfully slow and mired in bureaucracy. If we do not move faster, the bank points out, only around 40% of the countries on the continent will achieve universal access to electricity by 2050.

Without urgent measures to address the massive power gap across sub-Saharan Africa, the continent will struggle to not only contain COVID-19 and future pandemics, but also maintain sustainable economic growth going forward. Even Africa’s most industrialised economy — South Africa — with an electrification rate close to 90% — is being hammered by increasingly frequent and severe bouts of load shedding, disrupting the country’s post-COVID economic recovery prospects. Accelerating investment in cost-competitive and employment-creating renewables will be key here.

The South African government’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) indicates that the country needs 26 000 MW of new solar and wind capacity by 2030 to keep the lights on. Minister Gwede Mantashe’s announcement on 18 March of the preferred bidders for the Risk Mitigation IPP Procurement Programme, the launch of the fifth renewable energy IPP bidding window, and the announced licensing exemption for plants below 10MW, will go some way towards fulfilling the urgent requirement to rapidly expand South Africa’s energy generation capacity.

Nevertheless, emergency power procurement was always going to deliver sub-optimal outcomes for South Africa - as we've seen across Africa. While the inclusion of renewable energy capacity is encouraging, there are serious questions that need to be answered regarding the design and implementation of the procurement programme, especially the parameters seeming to favour gas plants (running at unnecessarily high capacity factors) and the treatment of local content requirements. There is really no clearer indictment of the country’s energy planning failures than having three power ships anchored in our harbours for 20 years.

The minister's lifting of the generation licensing cap is likewise both encouraging and disappointing, as there have been loud and clear calls from industry, academia and even Eskom to increase this to 50MW.

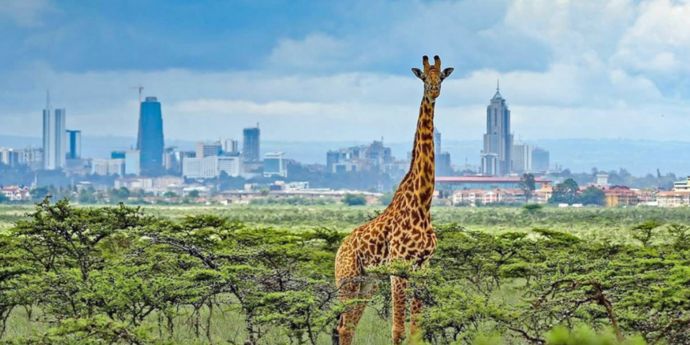

Whether Africa can reach its potential and compete globally will largely depend on how it positions itself to take advantage of the rapid shift to cheap renewable energy that is under way in the rest of the world.

But the energy needs of the continent — green or otherwise — require huge funding commitments. Previous estimates highlight that the cost of closing the energy access gap in sub-Saharan Africa's could be around $41bn a year, or about 6% of the region’s GDP. South Africa alone needs to invest a trillion rand in the next decade to restore energy security. Most of this funding will need to come from the private sector, as public finances are already stretched and now being diverted to dealing with the pandemic and its impacts.

Project finance plays a key role in financing private power projects — especially in emerging economies. These financing deals usually involve several investors (e.g., shareholders/equity investors, banks, pension funds and development finance institutions) that are paid back from the cash flows generated by the project. This approach is able to ease investment risk and raise finance at a fairly low cost, to the benefit of investors and consumers alike. To reap the benefits of power project financing, however, the continent needs energy professionals who are well versed in the fundamentals of power project finance, contracts and risk mitigation.

Africa has many of the ingredients to be an economic powerhouse, especially with the recently concluded African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AfCFTA) now operational. But without reliable power supply the continent will be unable realise its full potential.

We have a way to go, and the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic can be an opportunity to urgently increase energy security by accelerating power sector investment. It is literally, a life-or-death matter.

Wikus Kruger is a PhD Candidate, Research Fellow, and Course Convenor at the UCT GSB Power Futures Lab. He convenes the “Finance, contracts and risk mitigation for private power investment in Africa” short course running from 17 — 28 May 2021: https://www.gsb.uct.ac.za/powe...