Eskom’s new CEO Andre de Ruyter says it will take time to solve the South Africa energy situation. But as a new CSIR report chillingly points out - time is not on our side.

A recent report by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) shows the urgency of signing off on significant policy and regulatory decisions by at least March 2020 to ensure sufficient electricity supply for the country’s economy.

Last year was South Africa’s worst-ever year of load shedding and cost the economy between R60bn and R120bn. But unless major changes are made, we may be in for even more severe power cuts ahead. The CSIR points out that the energy shortfall is even bigger than assumed in government’s Integrated Resource Plan 2019 (IRP), which already identified significant capacity and energy shortages in the short- to medium-term.

Not only is there is little hope that Eskom’s power plant performance will improve enough to ward off the crisis, but the key decisions needed to ensure the long-term health of the sector are not being implemented. One of the first objectives of Minister of Public Enterprise, Pravin Gordhan’s road map for restructuring Eskom was to have a separate transmission company established by March this year. New Eskom CEO Andre De Ruyter’s announcement that more time is needed to implement government’s proposed unbundling of the state utility is a worrying sign that we are in for more of the same as the incumbent seeks to protect its interests at all costs. Meanwhile Finance Minister Tito Mboweni’s attempts to reassure international visitors at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland, were not entirely convincing, with commentators like CNN’s Business Editor, Richard Quest, saying, “At the end of the day there's no point in coming here to say, 'Invest, invest, invest in me if you haven't got the policies worthy of it'."

This is really the crux of the matter. Enabling investment is the easiest and most efficient way to address the country’s electricity supply problem. The use of renewable energy is increasing rapidly in South Africa, as in the rest of Africa, driven by rapidly falling technology costs. Renewables now have a proven track-record of reducing pressure on the grid and providing cleaner — and cheaper — electricity. Bids by private power developers in international and African renewable energy procurement programmes have broken electricity cost records several times in the past year and now represent the cheapest source of new power in most countries in the region — including South Africa.

There is little doubt that if South Africa were to launch a new round of procurement for renewable energy IPPs, the resulting projects would produce power at costs lower than many of Eskom’s existing coal plants. Operating South African renewable energy IPPs — representing more than 3000 MW — have on average also taken less than two years (and in some cases only one year) — to build. This is, again, in stark contrast with the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power plants, both of which are still not finished (Medupi is now scheduled for 2021 and Kusile for 2023) and will not operate close to their rated capacity due to serious design flaws.

However, as Minister Mboweni discovered in Davos, attracting investors for these projects is not going to be a straightforward process in the current climate. Private power investment is a risky endeavour. Investors need to borrow and invest enormous amounts of capital in an asset that cannot be moved, and then repay their loans and try to make a return on investment based on monthly electricity sales over a period of 20 years to a state utility company that is usually in quite bad financial shape. On top of that, there is often a lack of expertise, trust and understanding on both sides of the negotiation table.

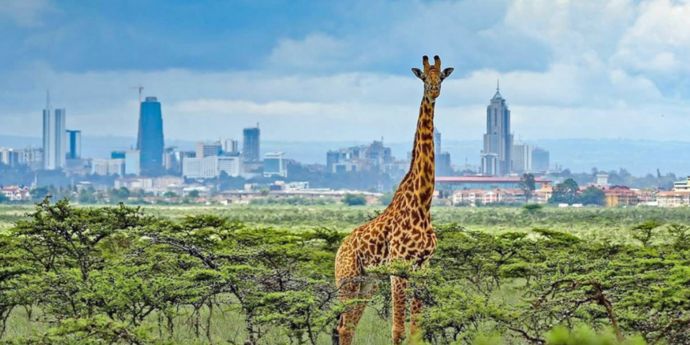

Ironically, South Africa’s neighbours including Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Eswatini, and Zimbabwe that rely on Eskom for more than half of their electricity needs, are pulling ahead by introducing new utility-scale private sector power procurement programmes. Namibia in particular has been very effective at bringing new private power capacity onto the grid at low cost and without burdening the national fiscus. The country has been able to power ahead due in large part to innovative financing and project risk mitigation solutions, developed through sophisticated partnerships between NamPower, commercial banks and development finance institutions. Having had almost no private participation in its power sector before 2016, Namibia now has the fourth most IPPs in sub-Saharan Africa — a remarkable achievement in such a short period.

The success of these kinds of programmes depends on the extent to which decision-makers understand the fundamentals of contractual agreements and partnerships between public and private entities, looking in particular at how risks are allocated and mitigated. Demand for professionals with a sophisticated appreciation of the technical, legal and financial requirements for these types of investments is likely to rise as the continent increasingly moves in this direction. 280 IPPs representing 20 GW of installed capacity are operating or being built in sub-Saharan Africa. Much more is needed to meet growing energy demand.

In South Africa, there is no time to waste. The CSIR study authors state very clearly that there is a “…need for urgency in making the decisions required to ensure that capacity comes online timeously. In fact, in our estimation, all these decisions and actions need to be taken before the end of the first quarter.” This clearly shows that the time for talking is over — the time for taking action has arrived.

Wikus Kruger is a junior research fellow at the UCT Graduate School of Business Power Futures Lab and convenes the Finance, Contracts and Risk Mitigation for Private Power Investment in Africa (Power Sector Financing).