The first COVID-19 vaccines have arrived in South Africa amid much fanfare — drowning out the voices of those asking why we are paying double for them in the first place and why they are unlikely to help those who need them most.

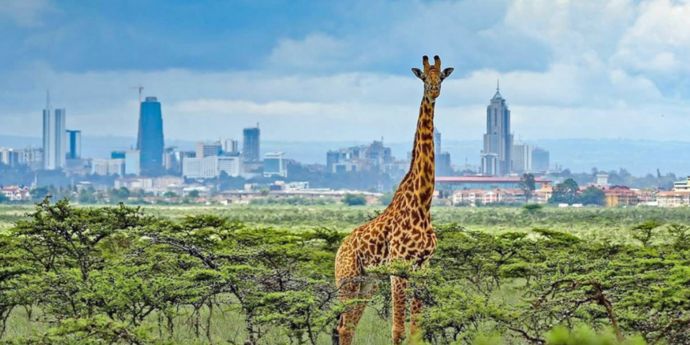

Up to 70 countries will only be able to vaccinate one in 10 people against COVID-19 this year due to the high cost of the vaccines and their lack of availability, according to a new report from Oxfam. In what’s being called a “global vaccine apartheid”, wealthier nations (like Canada) are buying up vaccine doses to vaccinate their populations up to five times over, while others (like South Africa) are having to pay almost 2.5 times more for vaccines and still don’t have enough to go around.

This disparity has led organisations like Amnesty International, Frontline AIDS, Global Justice Now and OXFAM to raise the red flag and join forces in a People’s Vaccine Alliance. Their aim: to campaign for better access to vaccines and for pharmaceutical corporations to share their technology through the World Health Organisation COVID-19 Technology Access Pool, to enable the manufacture of billions more doses for all who need them.

The UCT GSB Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship has pledged its support for the C19 People’s Coalition, with centre director Solange Rosa saying the People’s Vaccine Campaign recognises that COVID-19 vaccination is not only a medical issue but a social justice imperative that cuts very close to the bone in South Africa.

A deepening chasm between rich and poor

In 2019, the World Bank named South Africa the most unequal country in the world and COVID-19 has exacerbated the divide. Amid strict lockdown measures, the pandemic has forced millions into unemployment — at least 250 000 domestic workers have lost their jobs, many of them single mothers without savings or an ability to work from home. Poverty and unemployment have increased, and with children dropping out of school due to a lack of technology resources to enable them to study at home, and parents unable to pay fees, there are fears that an entire generation of young learners will be lost.

At a macroeconomic level, entire sectors are floundering and up to 60% of SMEs are in danger of having to shut up shop. The hospitality and entertainment industry, for instance, record losses daily; during the peak holiday season in December 2020, many hotels were operating at between just 30% to 50% occupancy.

South Africans are hanging on by their fingertips, and inequitable access to the vaccine will make things worse. While President Cyril Ramaphosahas said more vaccines are coming, it is not clear when and how many will arrive. Vaccination plans have been submitted and 200 vaccination sites identified, but there is much public confusion and misinformation regarding the vaccines.

Learning from the past

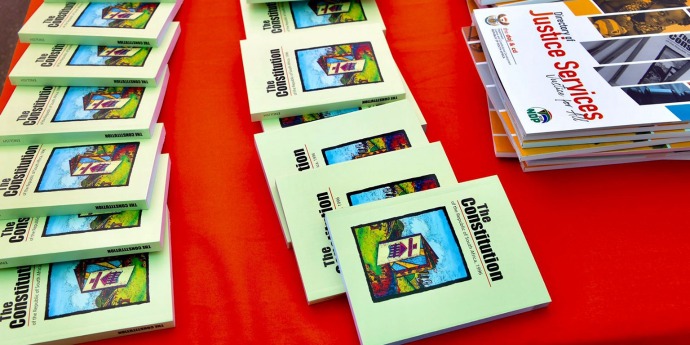

To many in the healthcare sector, the situation is all too familiar. Many will recall how South Africa took six years to put in place antiretroviral treatment for HIV/Aids patients while thousands needlessly died. This mirrored a global struggle to improve treatment for HIV/AIDS patients. The UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board heard recently how communities engaged with global health authorities for over 25 years to advocate for those living with HIV/Aids. This work paid off in several ways including with the development of the Medicine Patent Pool for HIV,which saw the manufacture of millions of cost-effective antiretrovirals and brought down costs for medication from about $10 0000 per year to $100.

There is a lesson here about how a concerted and a unified campaign aimed at global health authorities can be brought to bear on the vaccine response for COVID-19. And this does not have to come at the expense of profits for the pharmaceutical companies — or take a quarter of a century — as we have the example of those who have gone before us to show us the way. The message has to be communicated loudly, clearly and insistently: There can be no social justice without equitable access to vaccines and critical treatments.

Taking action in three key areas

The international campaign for a people’s vaccine is gathering pace. Here in South Africa, Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, acting on behalf of the Campaign, wrote to high-level US experts a few days ago, appealing to the US government — that co-owns and co-produces the NIH-Moderna vaccine — to ensure that Moderna produces more vaccines and shares its technology with the World Health Organisation.

And on the ground, more can be done to optimise what we have. First, there is an opportunity to dramatically scale up the role of community health workers (CHWs). Their efficacy in times of crisis is well-documented. During the Ebola pandemic in Liberia in 2014, for example, CHWs went door-to-door in areas, offering assistance and help where it was most needed. They were also able to supply vital information to authorities, which was used to bring the disease under control. Upskilling community workers in South Africa as professional cadres and including them in healthcare campaigns could help with vaccine roll-out here as well as with testing and tracing and even with a mass education campaign to address the rise of vaccination disinformation.

Second, it is critical to address the health crisis that is happening at our borders, where many South African citizens as well as foreign nationals are being held in quarantine in terrible conditions. There are also questions around the vaccination of non-South African residents and the estimated millions of undocumented migrants in South Africa from all over the African continent. There is currently no clarity on how they will gain access to vaccines.

Third, this is no time to go it alone. We need a multisectoral approach that includes government and the private sector as well as community leaders, trade unions, rural groups, and NGOs. We need to start conversations about the best solutions and look at how partnerships can help improve solutions. Corporations with social justice and development fund portfolios have a special role to play here to help fund vaccine doses and rollout. There are already examples of help coming from corporates, for example, MTN has donated R380m to the African Union to source seven million vaccines.

Ultimately, South Africa’s success or failure is not a country-issue. In their scramble to vaccinate their own populations, wealthier countries are missing an obvious lesson in how systems work; Everything is interconnected — as the pandemic has shown us all too clearly. A failure to ensure that all the world is safely vaccinated will ultimately come back to haunt all nations; the longer the virus is allowed to spread unchecked, the greater the chances of mutations that could render the vaccines we do have less efficacious.

As UNAIDS executive director Winnie Byanyima has so powerfully stated: Almost every business on the planet has had to step away from business as usual as a result of this pandemic. It is in all our interests that pharmaceutical companies, government and corporations now do the same. And each of us has a role to play in urging key role-players to throw their weight behind the growing call for a people’s vaccine. No one is safe until everyone is safe.

Get involved with the Bertha Centres’s drive for people’s vaccine. Find out what needs to be done to have the COVID-19 vaccine declared a public good. For more information, click here.

Katusha de Villiers is the Health Systems Innovation Lead at the UCT GSB Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship.